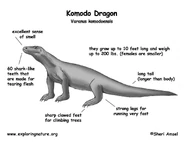

Komodo Dragon

The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), also known as the Komodo monitor, is a large species of lizard found in the Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, Gili Motang, and Padar. A member of the monitor lizard family Varanidae, it is the largest living species of lizard, growing to a maximum length of 3 metres (10 ft) in rare cases and weighing up to approximately 70 kilograms (150 lb).

Their unusually large size has been attributed to island gigantism, since no other carnivorous animals fill the niche on the islands where they live. However, recent research suggests the large size of Komodo dragons may be better understood as representative of a relict population of very large varanid lizards that once lived across Indonesia and Australia, most of which, along with other megafauna, died out after the Pleistocene. Fossils very similar to V. komodoensis have been found in Australia dating to greater than 3.8 million years ago, and its body size remained stable on Flores, one of the handful of Indonesian islands where it is currently found, over the last 900,000 years, "a time marked by major faunal turnovers, extinction of the island's megafauna, and the arrival of early hominids by 880 ka [kiloannums]."

As a result of their size, these lizards dominate the ecosystems in which they live. Komodo dragons hunt and ambush prey including invertebrates, birds, and mammals. It has been claimed that they have a venomous bite; there are two glands in the lower jaw which secrete several toxic proteins. The biological significance of these proteins is disputed, but the glands have been shown to secrete an anticoagulant. Komodo dragon group behaviour in hunting is exceptional in the reptile world. The diet of big Komodo dragons mainly consists of deer, though they also eat considerable amounts of carrion. Komodo dragons also occasionally attack humans in the area of West Manggarai Regency where they live in Indonesia.

Mating begins between May and August, and the eggs are laid in September. About 20 eggs are deposited in abandoned megapode nests or in a self-dug nesting hole. The eggs are incubated for seven to eight months, hatching in April, when insects are most plentiful. Young Komodo dragons are vulnerable and therefore dwell in trees, safe from predators and cannibalistic adults. They take 8 to 9 years to mature, and are estimated to live up to 30 years.

Komodo dragons were first recorded by Western scientists in 1910. Their large size and fearsome reputation make them popular zoo exhibits. In the wild, their range has contracted due to human activities, and they are listed as vulnerable by the IUCN. They are protected under Indonesian law, and a national park, Komodo National Park, was founded to aid protection efforts.

As with other varanids, Komodo dragons have only a single ear bone, the stapes, for transferring vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the cochlea. This arrangement means they are likely restricted to sounds in the 400 to 2,000 hertz range, compared to humans who hear between 20 and 20,000 hertz. It was formerly thought to be deaf when a study reported no agitation in wild Komodo dragons in response to whispers, raised voices, or shouts. This was disputed when London Zoological Garden employee Joan Proctor trained a captive specimen to come out to feed at the sound of her voice, even when she could not be seen.

The Komodo dragon can see objects as far away as 300 m (980 ft), but because its retinas only contain cones, it is thought to have poor night vision. The Komodo dragon is able to see in colour, but has poor visual discrimination of stationary objects.

The Komodo dragon uses its tongue to detect, taste, and smell stimuli, as with many other reptiles, with the vomeronasal sense using the Jacobson's organ, rather than using the nostrils. With the help of a favorable wind and its habit of swinging its head from side to side as it walks, a Komodo dragon may be able to detect carrion from 4–9.5 km (2.5–5.9 mi) away. It only has a few taste buds in the back of its throat. Its scales, some of which are reinforced with bone, have sensory plaques connected to nerves to facilitate its sense of touch. The scales around the ears, lips, chin, and soles of the feet may have three or more sensory plaques.

The Komodo dragon prefers hot and dry places, and typically lives in dry, open grassland, savanna, and tropical forest at low elevations. As an ectotherm, it is most active in the day, although it exhibits some nocturnal activity. Komodo dragons are solitary, coming together only to breed and eat. They are capable of running rapidly in brief sprints up to 20 km/h (12 mph), diving up to 4.5 m (15 ft), and climbing trees proficiently when young through use of their strong claws. To catch out-of-reach prey, the Komodo dragon may stand on its hind legs and use its tail as a support. As it matures, its claws are used primarily as weapons, as its great size makes climbing impractical.

For shelter, the Komodo dragon digs holes that can measure from 1 to 3 m (3.3 to 9.8 ft) wide with its powerful forelimbs and claws. Because of its large size and habit of sleeping in these burrows, it is able to conserve body heat throughout the night and minimise its basking period the morning after. The Komodo dragon hunts in the afternoon, but stays in the shade during the hottest part of the day. These special resting places, usually located on ridges with cool sea breezes, are marked with droppings and are cleared of vegetation. They serve as strategic locations from which to ambush deer.

Komodo dragons are carnivores. Although they eat mostly carrion, they will also ambush live prey with a stealthy approach. When suitable prey arrives near a dragon's ambush site, it will suddenly charge at the animal and go for the underside or the throat. It is able to locate its prey using its keen sense of smell, which can locate a dead or dying animal from a range of up to 9.5 km (5.9 mi). Komodo dragons have been observed knocking down large pigs and deer with their strong tails.

Komodo dragons eat by tearing large chunks of flesh and swallowing them whole while holding the carcass down with their forelegs. For smaller prey up to the size of a goat, their loosely articulated jaws, flexible skulls, and expandable stomachs allow them to swallow prey whole. The vegetable contents of the stomach and intestines are typically avoided. Copious amounts of red saliva the Komodo dragons produce help to lubricate the food, but swallowing is still a long process (15–20 minutes to swallow a goat). A Komodo dragon may attempt to speed up the process by ramming the carcass against a tree to force it down its throat, sometimes ramming so forcefully, the tree is knocked down. A small tube under the tongue that connects to the lungs allows it to breathe while swallowing. After eating up to 80% of its body weight in one meal, it drags itself to a sunny location to speed digestion, as the food could rot and poison the dragon if left undigested for too long. Because of their slow metabolism, large dragons can survive on as few as 12 meals a year. After digestion, the Komodo dragon regurgitates a mass of horns, hair, and teeth known as the gastric pellet, which is covered in malodorous mucus. After regurgitating the gastric pellet, it rubs its face in the dirt or on bushes to get rid of the mucus, suggesting it does not relish the scent of its own excretions.